Async JS Deep Dive: From Callback Queue to Microtasks

Master asynchronous JavaScript. We dive deep into the single-threaded nature, call stack, Web APIs, the event loop, and the crucial difference between the callback queue and microtasks.

If you’ve been writing JavaScript for a while, you’ve almost certainly encountered behavior that made you scratch your head. Maybe a setTimeout didn't fire exactly when you expected, or a Promise resolved sooner than you thought possible. You know JavaScript is "asynchronous," but what does that actually mean "under the hood"?

For intermediate developers, moving beyond just using async/await to truly understanding the machinery that powers it is a massive leveling-up moment. It turns debugging from a guessing game into a logical process.

Today, we’re going on a deep dive. We’ll go through the process of how a function works, from when you start it to how the browser decides what to do next.

1. Introduction to JavaScript's Single-Threaded Nature

Before we talk about asynchronous programming, we have to establish the ground rules.

JavaScript is a single-threaded, synchronous language.

This is the golden rule. It means that at any given instant, JavaScript can only be doing one thing. It has one main thread of execution. It reads your code line by line, executing one instruction, finishing it, and moving to the next.

If you're coming from multi-threaded languages like Java or C#, this sounds incredibly limiting. How can a complex web application handle user clicks, network requests, and intense calculations simultaneously if it can only do one thing at a time?

Imagine a busy coffee shop with only one barista. If that barista has to stop and wait for coffee beans to grow every time someone orders a latte, the line will never move. That’s "blocking."

In the browser world, if JavaScript stopped everything to wait for a server response (which could take seconds), your webpage would freeze. You couldn't scroll, click buttons, or even close the tab. It would be a terrible user experience.

JavaScript solves this concurrency problem not by adding more threads, but by being smart about how it handles waiting. It outsources the heavy lifting.

2. The Call Stack Explained (LIFO)

To understand how JS manages its single thread, we need to look at the Call Stack.

The call stack is a fundamental data structure that records where in the program we are. If we step into a function, we push it onto the stack. If we return from a function, we pop it off the top of the stack.

It operates on a LIFO (Last In, First Out) principle. Think of it like a stack of pancakes. You add pancakes to the top, and you eat (remove) them from the top.

Let's trace a simple, synchronous example:

function multiply(a, b) {

return a * b;

}

function square(n) {

return multiply(n, n);

}

function printSquare(n) {

const squared = square(n);

console.log(squared);

}

printSquare(4);

Here is what happens in the JavaScript engine's call stack:

The script starts executing. A "Global Execution Context" is pushed onto the stack.

It hits printSquare(4). The printSquare function is pushed onto the stack.

Inside printSquare, it calls square(n). square is pushed onto the stack (sitting on top of printSquare).

Inside square, it calls multiply(n, n). multiply is pushed onto the top.

multiply does its math and returns. It is popped off the stack.

square receives the value and returns. It is popped off the stack.

Back in printSquare, it calls console.log. console.log is pushed on, executes, and is popped off.

printSquare finishes and is popped off.

The stack is empty (except for the global context).

This is beautiful and predictable. But what happens when something takes a long time?

3. Web APIs: The Browser's Helping Hands

Remember, the JavaScript engine (like V8 in Chrome) is just one part of the browser environment. The browser is powerful and has many other threads separate from the main JS thread.

These are exposed to us via Web APIs. These are not part of the JavaScript language itself; they are features provided by the browser (or the Node.js runtime environment) that JavaScript can interact with.

Common Web APIs include:

setTimeout and setInterval (Timers)

fetch and XMLHttpRequest (Network requests)

The DOM (Document Object Model events like clicks, scrolling)

Geolocation, LocalStorage, etc.

When you call one of these functions, JavaScript is essentially saying to the browser: "Hey, take this task. I don't have time to wait for it. Do it in the background, and let me know when you're done."

Let's look at the classic example that confuses every beginner:

console.log(”Start”);

setTimeout(function cb() {

console.log(”Timer done”);

}, 2000);

console.log(”End”);Output:

Start

End

Timer doneHow did "End" print before "Timer done"?

console.log("Start") is pushed to the call stack, executed, and popped.

setTimeout is pushed to the stack. The JS engine sees this is a Web API call. It passes the callback function (cb) and the timer duration (2000ms) to the browser's Timer API.

Crucially, the setTimeout function itself completes immediately. It is popped off the stack. JavaScript moves on. It does not wait 2 seconds.

console.log("End") is pushed, executed, and popped.

The call stack is now empty.

Meanwhile, outside of the JS thread, the browser is counting down 2 seconds.

4. Callback Queue (Task Queue)

So, 2 seconds pass. The browser's Timer API finishes its countdown. What happens to that callback function cb we passed it?

The Web API cannot just shove the callback straight back onto the Call Stack. If it did, it might interrupt code currently running, causing chaos.

Instead, the completed callback is placed in a holding area called the Callback Queue (also known as the Task Queue or Macrotask Queue).

This queue is a FIFO (First In, First Out) structure. The first callback to finish waiting gets in line first.

In our previous example, after 2 seconds, the cb function ("Timer done") is sitting patiently in the Callback Queue, waiting for its turn to run.

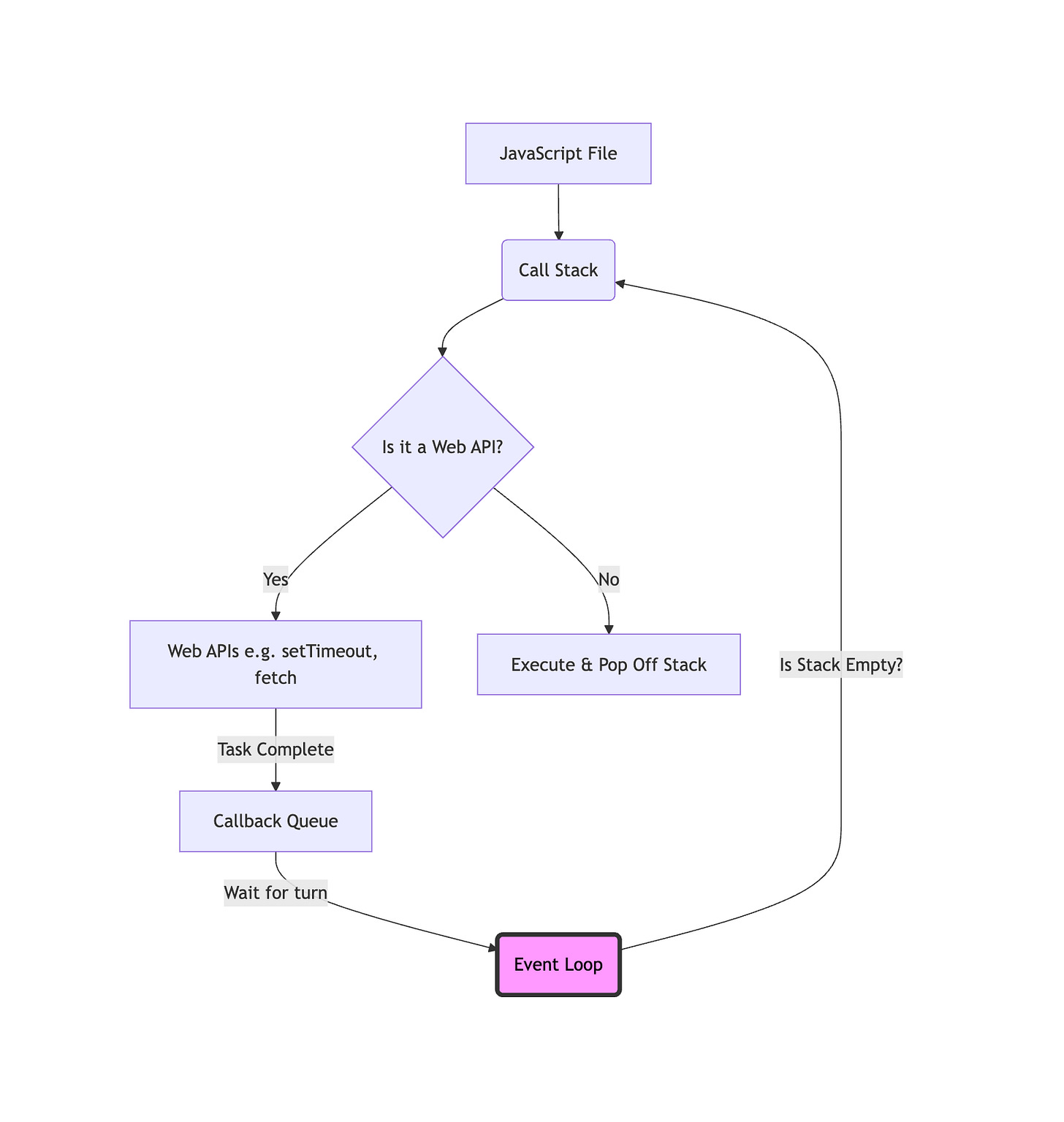

5. The Event Loop

This is the piece that ties everything together. The Event Loop is a constant process that acts as the conductor of this orchestra.

The Event Loop has a very simple, incredibly important job. It constantly checks two things:

Is the Call Stack empty?

Does the Callback Queue have anything in it?

If the Call Stack is not empty, the Event Loop does nothing. It waits. The current function must finish.

If the Call Stack is empty, and there are callbacks waiting in the Callback Queue, the Event Loop takes the first callback from the queue and pushes it onto the Call Stack, effectively running it.

Let's visualize the flow:

Diagram: The basic Event Loop flow.

Going back to our setTimeout example:

"Start" and "End" are printed. The Call Stack empties.

The browser finishes the 2-second timer and puts cb into the Callback Queue.

The Event Loop notices the stack is empty. It checks the queue, sees cb.

It moves cb to the Call Stack.

cb executes, printing "Timer done".

This explains why setTimeout(fn, 0) doesn't execute immediately. It still has to go to the Web API, then the Callback Queue, and wait for the stack to clear. It just means the "minimum waiting time" is zero ms.

6. The Gotcha: Microtasks and Priority

If you stop reading now, you have a solid understanding of traditional async JS. But modern JavaScript (Promises) introduced a wrinkle that you must understand: the Microtask Queue.

Not all asynchronous tasks are created equal.

Macrotasks (Task Queue): setTimeout, setInterval, setImmediate (Node), I/O, UI rendering.

Microtasks: Promise callbacks (.then, .catch, .finally), queueMicrotask, process.nextTick (Node - technically has its own super-priority queue, but behaves similarly for this concept).

The Microtask Queue is a separate VIP line. It sits alongside the Callback (Macrotask) Queue.

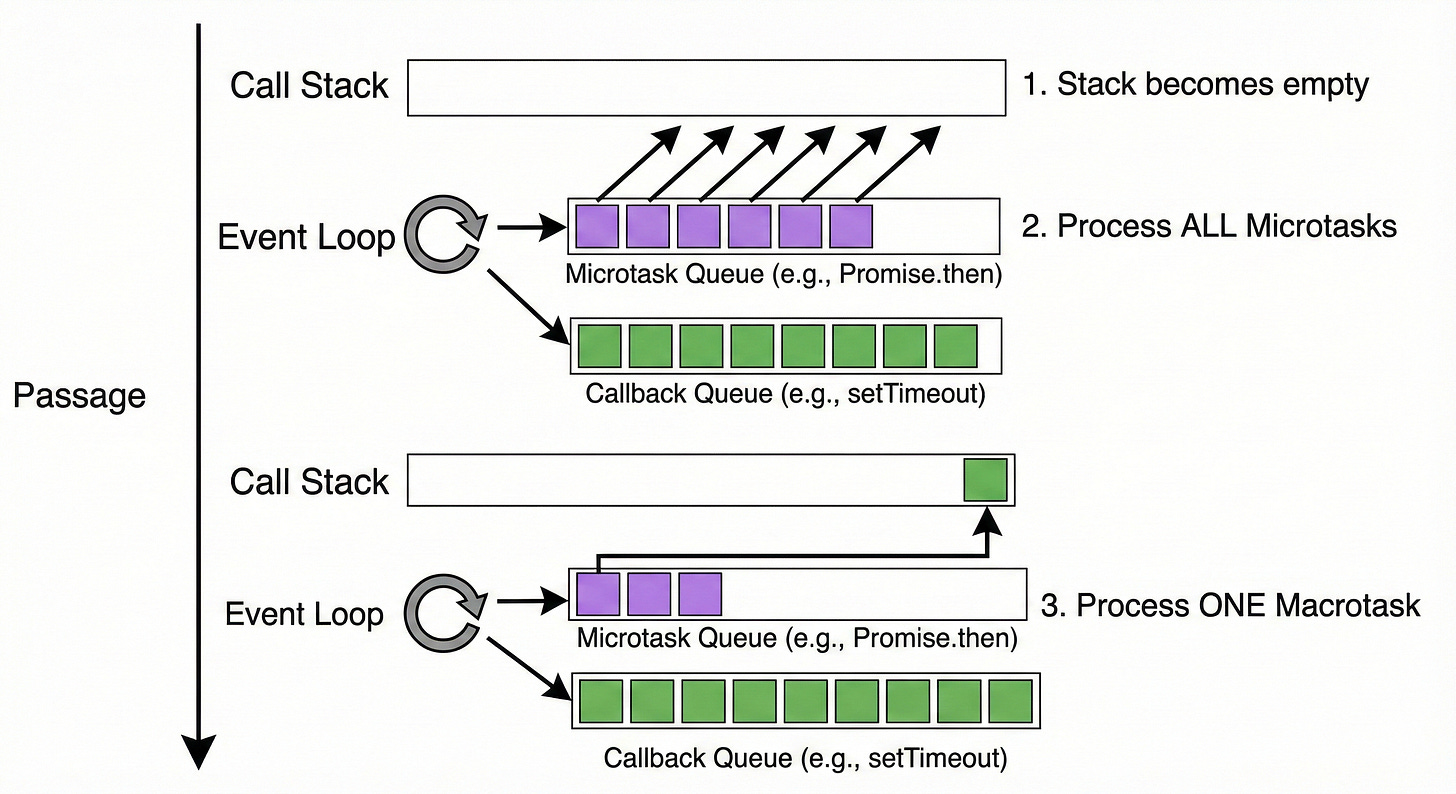

The crucial difference in the Event Loop:

When the Call Stack becomes empty, the Event Loop doesn't immediately look at the Callback Queue.

First, it checks the Microtask Queue.

It will execute every single item in the Microtask Queue until it is completely empty.

Only then will it move one item from the Macrotask Queue to the stack.

Furthermore, if a microtask adds another microtask during its execution, that new microtask is added to the back of the current queue and will be executed in the same cycle, before any macrotasks. You could theoretically create an infinite loop of microtasks and block the Event Loop forever!

Visualizing Microtask Priority:

Diagram: The priority flow. Microtasks always cut in line.

Let's look at the ultimate interview question example:

console.log(’1: Start’);

setTimeout(() => {

console.log(’2: setTimeout’);

}, 0);

Promise.resolve().then(() => {

console.log(’3: Promise 1’);

}).then(() => {

console.log(’4: Promise 2’);

});

console.log(’5: End’);Before scrolling down, try to predict the exact order of output.

...

...

...

The Execution Trace:

console.log('1: Start') -> Pushed to stack, executes, popped. Output: 1: Start

setTimeout -> Pushed to stack. It's a Web API. The timer (0ms) starts immediately, and its callback is moved to the Macrotask Queue.

Promise.resolve().then(...) -> Pushed to stack. The promise resolves immediately. Its .then() callback is moved to the Microtask Queue.

console.log('5: End') -> Pushed to stack, executes, popped. Output: 5: End

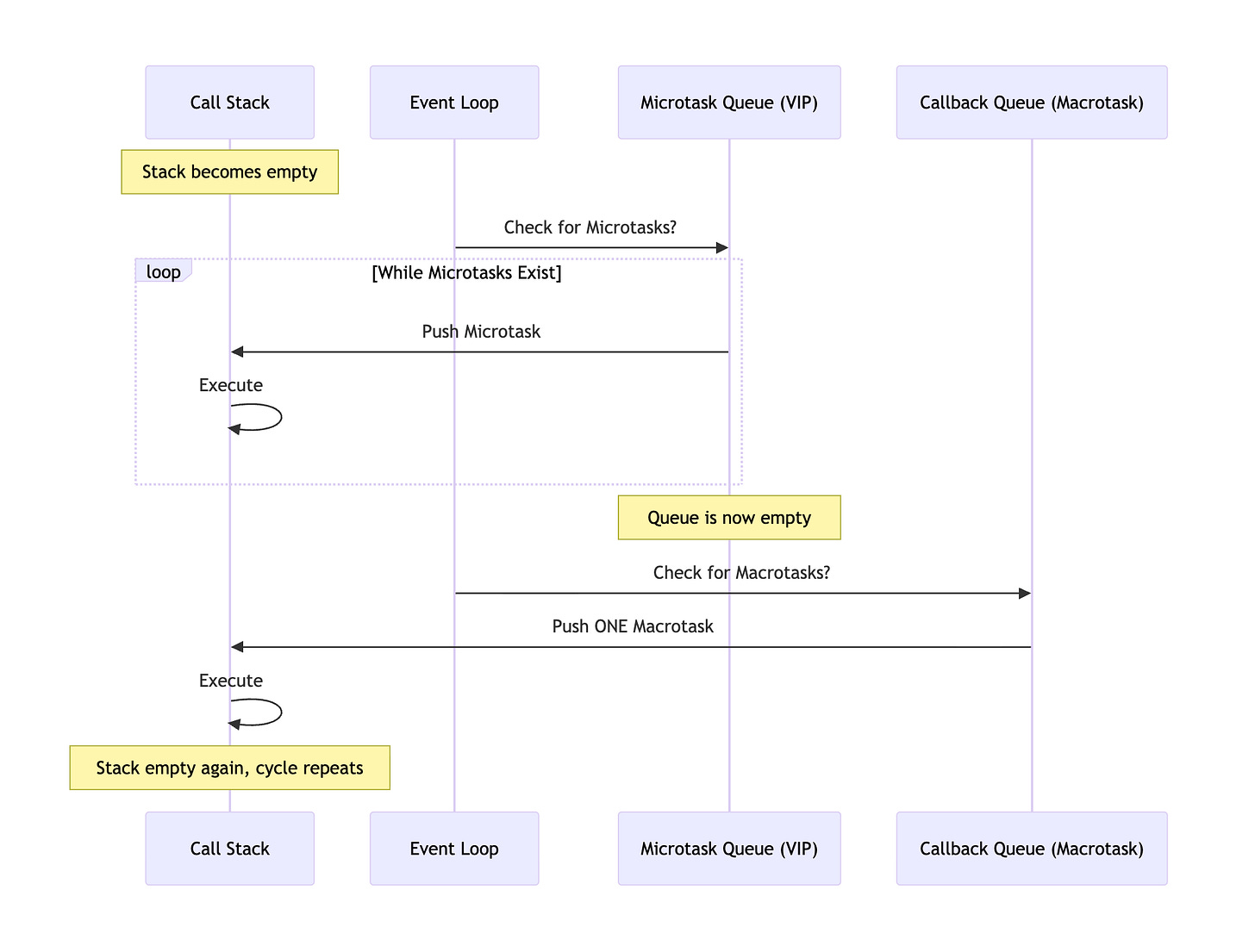

The Call Stack is now empty. The Event Loop wakes up.

Priority Check: Event Loop checks the Microtask Queue first. It finds the first Promise callback.

It moves it to the stack. It executes, printing Output: 3: Promise 1.

Crucial Step: This callback returns a new Promise (implicitly). The next chained .then() callback is added to the end of the Microtask Queue.

The stack is empty. Event Loop checks Microtask Queue again. It finds the second Promise callback.

It moves it to the stack. It executes. Output: 4: Promise 2.

The stack is empty. Event Loop checks Microtask Queue. It's empty.

Only now does the Event Loop check the Macrotask Queue. It finds the setTimeout callback.

It moves it to the stack. It executes. Output: 2: setTimeout.

Final Output:

1: Start

5: End

3: Promise 1

4: Promise 2

2: setTimeoutUnderstanding this priority difference is the key to mastering asynchronous flows in modern JavaScript applications. It explains why your React state updates might batch together, or why a fetch handler runs before a timeout even if they finished concurrently.

Practice these concepts:

To truly cement this knowledge, you need to get your hands dirty. Try these exercises:

Build a fetch chain: Create a function that makes 3 sequential API calls, where the second call depends on data from the first, and the third depends on the second. Use fetch and .then(). Then, rewrite it using async/await to see how much cleaner it is (but remember, it's still promises underneath!).

Debug execution order: Write a complex script mixing synchronous logs, setTimeout(0), a resolved Promise, and a queueMicrotask. Try to predict the output, run it, and explain why you were right or wrong.

Convert callback hell: Find an old example of deeply nested callback "hell" online (usually involving old Node.js fs operations or older AJAX examples). Refactor it completely into modern async/await syntax.

Share your async JS questions in the comments! Did the microtask queue surprise you? What's the hardest async bug you've ever had to squash? Let's discuss.

Based on concepts from these excellent resources:

Namaste JavaScript Ep.15 (YouTube) - Akshay Saini's incredible visual explanation.

DigitalOcean Event Loop tutorial - A thorough text-based deep dive.

Dev.to Call Stack explanation - Great primers on stack data structures.

MDN Web Docs - The definitive documentation for Promises and async/await.